A Closer Look at the “Societies of Thought” Paper

Introduction

Today I’m going to take a deep dive into an intriguing paper that just came out: Reasoning Models Generate Societies of Thought by Junsol Kim, Shiyang Lai, Nino Scherrer, Blaise Agüera y Arcas and James Evans. Here’s how co-author James Evans explains the core finding:

These models don’t simply compute longer. They spontaneously generate internal debates among simulated agents with distinct personalities and expertise—what we call “societies of thought.” Perspectives clash, questions get posed and answered, conflicts emerge and resolve, and self-references shift to the collective “we”—at rates hundreds to thousands of percent higher than chain-of-thought reasoning. There’s high variance in Big 5 personality traits like neuroticism and openness, plus specialized expertise spanning physics to creative writing. The structure mirrors collective intelligence in human groups. Moreover, toggling conversational features causally toggles this capacity—beneficial cognitive behaviors like verification become more likely when they can “inhabit” different personas.

That’s a pretty bold set of claims! How would you even measure personality in a reasoning trace?

At a high level, the paper is about something that I’ll refer to as Dialogue: the reasoning trace of an LLM often contains what appears to be a conversation between two or more distinct perspectives. What does Dialogue actually look like?

The paper is full of interesting findings, but the methods are just as interesting as the findings. We’ll walk through it in four stages, looking at what the authors found, how they found it, and what it means. In particular, we’ll see if they’re able to show that Dialogue improves reasoning ability, rather than just being correlated with it.

One: Measuring Dialogue

The authors identify a set of Dialogue features and use an LLM to score how often those features appear in each reasoning trace. They then compare how often Dialogue features appear in different circumstances.

Key findings:

- 1: Dialogue is more common in reasoning models than non-reasoning models.

- 2: Dialogue is more common when solving hard problems than easy problems.

Technical note: about “reasoning traces”

I’ll sometimes include technical details that are interesting but not vital. Feel free to skip them if you aren’t interested in the technical minutiae.

The paper looks primarily at reasoning models (which have reasoning traces), but also investigates non-reasoning models (which don’t normally have reasoning traces). To address that, they explicitly prompt the non-reasoning models to reason out loud in <think> </think> blocks and use those blocks as the “reasoning trace”.

Two: Measuring perspectives

The paper finds strong evidence of multiple implicit “perspectives” in the traces, each with distinct personality traits and expertise.

Key findings:

- 3: Reasoning models generate a larger number of perspectives.

- 4: Reasoning models generate more diverse perspectives.

Three: Testing causation via activation steering

The authors use a technique called activation steering to increase the activation of a “conversational surprise” feature that increases both Dialogue and reasoning ability.

Key findings:

- 5: Increasing the activation of a single feature in the model simultaneously increases both Dialogue and reasoning ability.

Four: Testing causation via training

Finally, the authors use some clever training experiments to explore whether Dialogue causally improves reasoning.

Key findings:

- 6: Training a model to solve Countdown tasks increases Dialogue, even though Dialogue is not explicitly trained for.

- 7: A model fine-tuned with Dialogue learns faster than a model fine-tuned with comparable monologue.

- 8: Fine-tuning the model on Dialogue about Countdown tasks increases its ability to learn to identify political misinformation.

Technical note: Countdown tasks

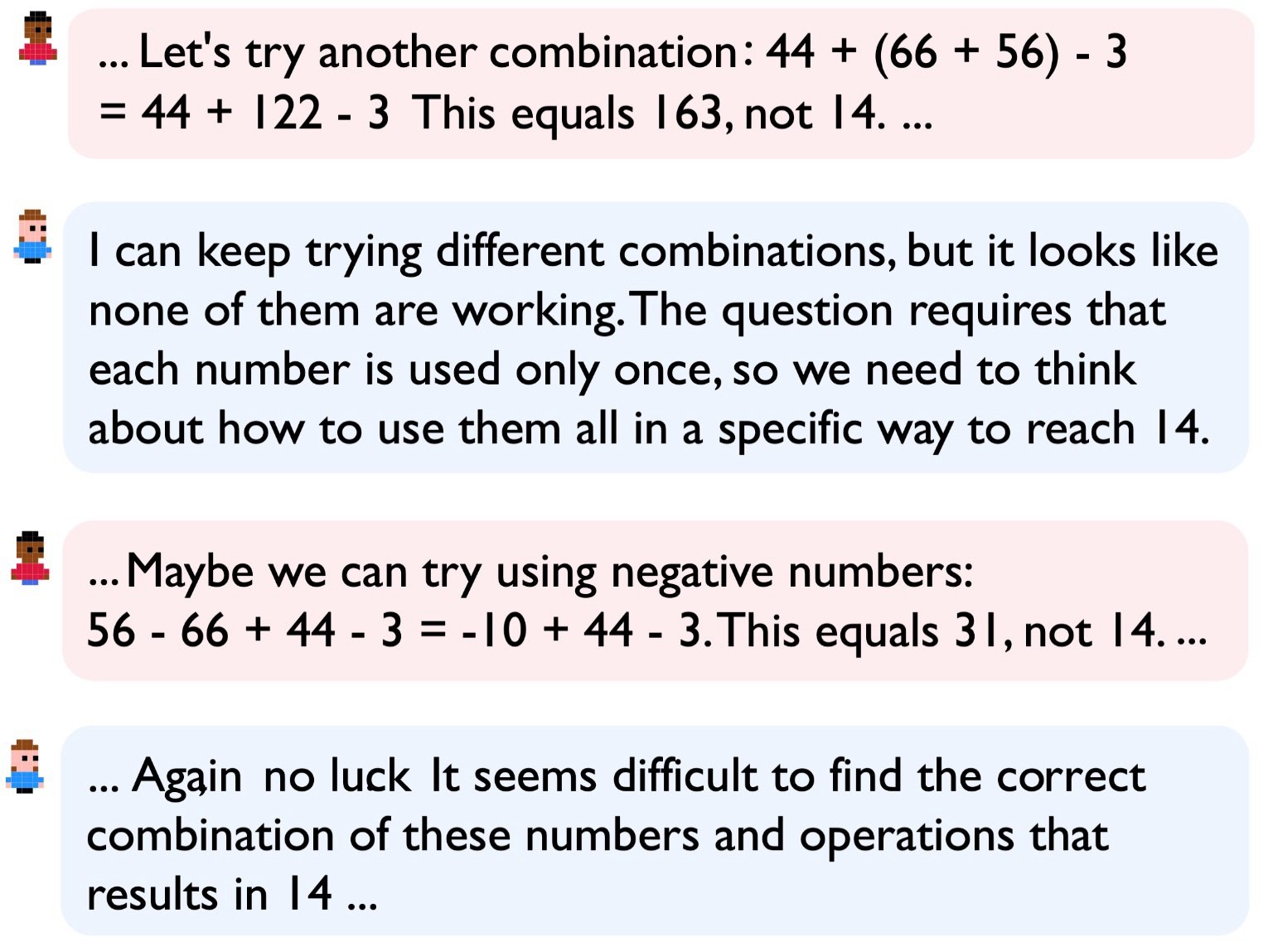

Countdown tasks are a type of challenging math problem. They’re popular in AI because they require the use of a variety of cognitive strategies. Here’s a typical example:

Your goal is to produce the number 853 by combining the numbers 3, 6, 25, 50, 75, and 100. You can use addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. You don’t have to use all the numbers, but you can use each one only once.

(The solution is: (75 + 50) x 6 + 100 + 3)

Yes, but what does it all mean?

Once we’ve walked through the key findings, we’ll talk about what it means—and, because it would be easy to misinterpret this paper, we’ll also talk about what it doesn’t mean.

Appendix: What didn’t we talk about?

This is a very technical paper: I’ve done my best to make it accessible, but it simply isn’t possible to present every single finding in a way that captures all of the technical nuance while remaining easily accessible to non-technical readers.

There were a few important topics that simply didn’t fit into the main body of this article, including some statistical methods and controls. I’ll talk briefly about them in the appendix, and point you at where to find them if you want to explore further.

But for now, let’s start at the beginning.

One: Measuring Dialogue

What is Dialogue, and how do you measure it?

The authors identify a set of conversational features like question answering and expressing disagreement, which I’ll refer to collectively as Dialogue features. They then have a separate LLM assess how often those features appear in each reasoning trace using a technique called LLM-as-judge.

Technical note: Dialogue features

I’m using the term “Dialogue features” as an umbrella term for both conversational behaviors and socio-emotional roles, which are treated separately in the paper.

The authors look at 4 conversational behaviors:

* Question-answering

* Perspective shifts

* Conflicts of perspectives

* Reconciliation of conflicting viewpoints

They also use Bales’ Interaction Process Analysis, which is commonly used in studies of human groups. There are 12 socio-emotional roles, grouped together into 4 categories:

* Asking for orientation, opinion, and suggestion

* Giving orientation, opinion, and suggestion

* Negative emotional roles (disagreement, antagonism, tension)

* Positive emotional roles (agreement, solidarity, tension release)

Technical note: LLM-as-judge

The authors use an LLM (Gemini 2.5 Pro) to score the reasoning traces. That raises an obvious question: how reliable is the LLM-as-judge technique?

They validate the technique by comparing it to a different LLM (GPT-5.2) as well as to human raters, finding strong agreement with both. I take that as evidence that they found something real (exactly what they found, and what it means, is less clear-cut).

Finding #1: Dialogue is more common in reasoning models than non-reasoning models

If Dialogue is an important part of reasoning, you’d expect that reasoning models would produce more Dialogue than non-reasoning models. That’s exactly what the authors find. They use the LLM-as-judge to measure what percentage of reasoning traces contain each Dialogue feature. They find that Dialogue features are dramatically more common in traces from reasoning models (see Fig. 1a and Fig. 1b).

Technical note: models and data

The models used were DeepSeek-R1-0528 (reasoning), DeepSeek-V3-0324 (non-reasoning), QwQ-32B (reasoning), Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct (non-reasoning), Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct (non-reasoning) and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct (non-reasoning).

It’s notable that they used two pairs of comparable models as well as non-reasoning models in a wide range of sizes, which increases the credibility of the findings.

There’s strong statistical work validating many of these results: see the appendix for further details.

Finding #2: Dialogue is more common when solving hard problems than easy problems

Next, the authors find that Dialogue is more common when a given model solves harder problems. For this analysis, they have the models solve a set of problems rated on a 7-point difficulty scale from 1 (extremely easy) to 7 (extremely hard). They then compare the average difficulty of problems where each feature does and does not appear. Dialogue features appeared in problems with an average difficulty of 3.6, compared to 2.3 for problems without those features—roughly the difference between a moderately challenging problem and a straightforward one. (Data estimated from Fig. 1e)

Technical note: problem sets and difficulty ratings

For much of the analysis, the authors used a curated set of 8,262 problems taken from a set of commonly used benchmarks (BigBench Hard, GPQA, MATH (Hard), MMLU-Pro, MUSR, and IFEval).

Some experiments used more specialized tasks, which we’ll talk about when we get to them.

Problem difficulty was assessed using two separate techniques:

* The LLM-as-judge directly assesses a difficulty rating for each problem.

* They give each problem to all four non-reasoning models and use their failure rate as an indication of difficulty.

Summary

We’re really just getting started. We’ve established what Dialogue is, and what specific Dialogue features we’ll be looking at throughout the rest of this piece.

We’ve also started to explore the connection between Dialogue and reasoning ability. There seems to be a strong correlation between the two: models that are better at reasoning use more Dialogue, and a given model uses more Dialogue when it has to think harder.

Two: Measuring perspectives

Finding conversational features seems straightforward enough, but how on earth do you identify and rate individual “perspectives”? Let’s turn our attention to some of the most surprising parts of the paper.

The authors were smart to choose the term “perspectives”: it keeps the focus on the conversational phenomena, while avoiding the anthropomorphic implications of a term like “personas”. They are consistently careful about this throughout the paper, which I appreciate.

The authors again use the LLM-as-judge, this time instructing it to:

- Count number of perspectives that appear in each trace

- Score the Big 5 personality traits of each perspective

- Generate a short free-form description of each perspective’s domain expertise

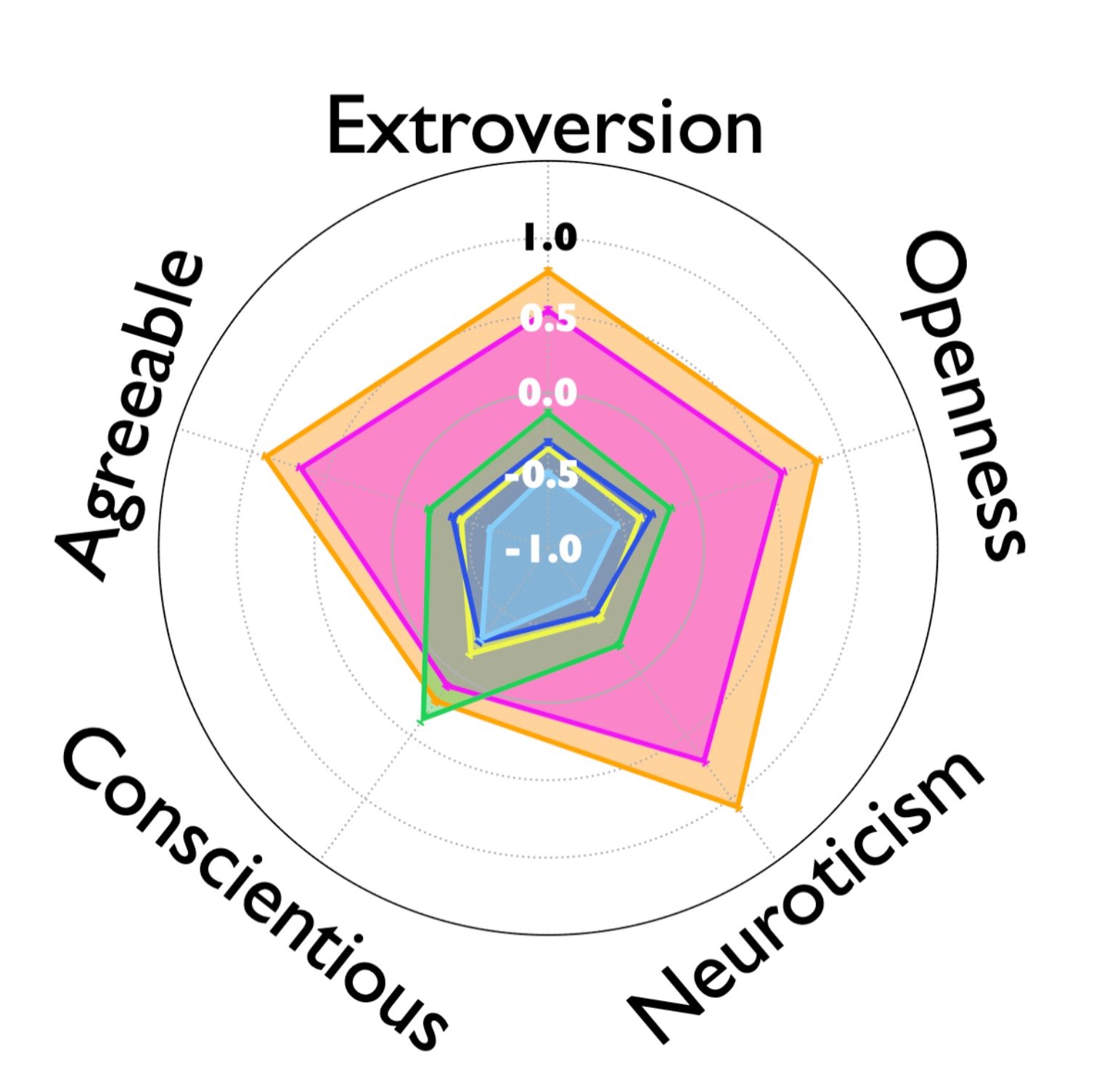

The Big 5 personality traits are commonly used in human psychology—they are Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (aka OCEAN). I want to be clear that the authors make no claim that there are actual personalities here—they’re using the Big 5 as a way to describe the behavior of the different perspectives.

Technical note: validating the LLM-as-judge

The authors are asking a lot of the LLM-as-judge in this section. How confident are we that it’s accurate? They’ve put real effort into validation, but some of the measures are better validated than others.

Their core technique is to assess the LLM-as-judge’s performance when evaluating the Intelligence Squared Debates Corpus (ISDC), a corpus of transcribed human debates. They find it does a reliable job of correctly identifying the speakers in a conversation, even when labels are removed and the text of the conversation is concatenated into a single block. This is strong validation that they’re able to correctly identify perspectives.

They further use the biographical information included in ISDC to show that the LLM-as-judge does a pretty good job of categorizing the diversity of domain expertise in a conversation. I find this work moderately convincing.

The Big 5 traits are scored using the widely used BFI-10 questionnaire. The paper doesn’t appear to validate the Big 5 scoring as rigorously as the other measures, so consider those results to be interesting but not in any way definitive.

Finding #3: Reasoning models generate a larger number of perspectives

The difference is pretty striking:

- Reasoning models average 2.9 perspectives per trace

- Non-reasoning models average 1.4 perspectives per trace

(Data estimated from Fig. 1d)

An average of 1.4 perspectives suggests that the non-reasoning models were often generating monologues, while 2.9 suggests something more like an exchange of viewpoints.

Finding #4: Reasoning models generate more diverse perspectives

The authors use some fairly technical statistics to measure the diversity of personality traits. I don’t think I’d do anyone any favors by trying to summarize those techniques here, but they clearly show that the reasoning models generate perspectives with much more diverse personality traits—except, interestingly, for conscientiousness. That trait was consistently high in all the models, which makes a certain amount of sense: presumably conscientiousness is always a desirable attribute.

The perspectives from reasoning models don’t just have more diverse personality traits: they also have much greater diversity of expertise.

Technical note: calculating diversity of expertise

Since the LLM-as-judge generates free-form descriptions of each perspective’s domain expertise, how do you calculate diversity of expertise?

The authors turn each expertise description into an embedding and calculate diversity as the mean cosine distance from the centroid of all embeddings.

Fig. 3b is a useful visualization of the embedding space of expertise, if you want to get a sense of what kinds of expertise were identified.

Summary

I was initially pretty skeptical about the claims in this section, but I think the authors have done strong work here.

I’m convinced that the authors are measuring something real and interesting when they calculate the number of perspectives, diversity of personality traits, and diversity of expertise. And I’m convinced that all of those metrics are higher in reasoning models, showing strong correlation between whatever they’re measuring and reasoning ability.

I’m not convinced, however, that we know exactly what is being measured. The analogies to human conversation are interesting and illuminating, but I don’t think there’s nearly enough here to say that the models are generating distinct entities with real personalities. (To be clear, the authors make no such claim.)

Three: Testing causation via activation steering

We’ve learned a lot about the nature of Dialogue and seen that it’s strongly correlated with reasoning performance. We now turn our attention to a pair of clever experiments that try to establish a causal relationship. We’ll begin with activation steering.

What is activation steering?

We don’t fully understand what happens inside LLMs, but modern interpretability techniques offer partial insight into their internal representations. In particular, a tool called a sparse autoencoder can identify features inside a model that seem to represent human concepts. By increasing or decreasing the activation of those features, we can steer some aspects of the model’s behavior.

As a demonstration of this technique, Anthropic developed Golden Gate Claude, which had a monomaniacal obsession with the Golden Gate Bridge. It was created by finding a feature that was associated with the Golden Gate Bridge and increasing its activation.

Technical note: what is a sparse autoencoder (SAE)?

LLMs store information in a distributed fashion, with each concept spread across many neurons, and each neuron having a role in understanding many concepts.

An SAE is a tool for untangling those patterns into something more understandable. It identifies internal activation patterns (called “features”) that correspond to human concepts like the Golden Gate Bridge, or deception.

You can use an SAE to get a sense of what the model is “thinking”—for example, SAEs have been used to tell when a model is being deceptive. It’s also possible to increase the activation of a feature.

Finding #5: Increasing the activation of a single feature in the model simultaneously increases both Dialogue and reasoning ability.

The authors explore whether it’s possible to increase Dialogue by activating particular features within the model, and whether doing so increases reasoning ability. It turns out that increasing the activation of randomly selected conversational features modestly increases both Dialogue and accuracy.

Going further, the authors zeroed in on a specific feature (Feature 30939), which is “a discourse marker for surprise, realization, or acknowledgment”. They find that increasing the activation of Feature 30939 doubles accuracy on Countdown tasks and substantially increases the prevalence of multiple Dialogue Features.

The paper also finds that increasing the activation of Feature 30939 increases the diversity of internal feature activations related to personality and expertise, strengthening the theory that perspective diversity is an integral part of Dialogue.

The authors further strengthen these results with a mediation analysis—it’s beyond the scope of this article, but I discuss it briefly in the appendix.

Summary

The fact that activating a single feature increases multiple measures of Dialogue while simultaneously increasing reasoning ability is further evidence that Dialogue directly affects reasoning ability. It isn’t definitive, though: this experiment can’t rule out the possibility that Dialogue and reasoning are independent results of some unknown internal process.

The case is getting stronger, but we aren’t quite there yet.

Four: Testing causation via training

Finally, the authors test the relationship between Dialogue and reasoning ability with a set of training experiments. These experiments are very nicely designed and present the strongest evidence that Dialogue directly improves reasoning.

The core experiment trains a small base model to solve Countdown tasks. The training rewards the model for accuracy and correctly formatted output, but not for Dialogue.

Technical note: methods

This experiment uses Qwen-2.5-3B, a small pre-trained model without any instruction-tuning. They also replicate the results with Llama-3.2-3B.

Training consists of 250 steps of reinforcement learning (RL) on Countdown tasks.

Finding #6: Training a model to solve Countdown tasks increases Dialogue, even though Dialogue is not explicitly trained for

Over the course of training, problem-solving accuracy increases from approximately 0% to 58%. At the same time, the frequency of Dialogue features increases sharply.

This strongly suggests that Dialogue emerges spontaneously during training because it’s a useful problem-solving strategy.

Finding #7: A model fine-tuned with Dialogue learns faster than a model fine-tuned with comparable monologue

The authors have one more trick up their sleeve, and it’s perhaps the strongest single piece of evidence. They use a technique called fine-tuning, which pre-trains the model with additional examples. They compare the learning performance of the baseline model to two fine-tuned versions:

- The Dialogue version is fine-tuned on examples of Dialogue about Countdown tasks.

- The monologue version is fine-tuned on examples of monologue about Countdown tasks.

During subsequent training, the fine-tuned models both learn faster than the baseline model, but the Dialogue-tuned model learns fastest. All three models begin with an accuracy of very close to 0%, but by step 40 of training, their accuracy levels have diverged:

- Baseline model: 6%

- Monologue-tuned model: 28%

- Dialogue-tuned model: 38%

This is a compelling result: both models received similar Countdown content—the only difference was the format. The fact that the Dialogue-tuned model learns significantly faster strongly suggests that Dialogue directly contributes to the ability to learn.

Finding #8: Fine-tuning the model on Countdown task Dialogue increased its ability to learn to identify political misinformation

For the final experiment, the authors compare the learning rates of the baseline model and the Dialogue-tuned model.

Both models are subsequently trained to identify political misinformation. The model that was fine-tuned on Dialogue learns faster than the other model, even when learning a very different task. This transfer between domains provides further compelling evidence for the causal role of Dialogue in learning problem-solving skills.

Technical note: variation between models

These are compelling results, though I note significant variation between the primary results with Qwen-2.5-3B and the replication with Llama-3.2-3B.

Extended Data Fig. 8 shows that with Qwen-2.5-3B, the models that were fine-tuned on Dialogue and monologue ultimately converged to almost the same accuracy, while no such convergence occurred with Llama-3.2-3B.

Summary

I had a great time reading about these very elegant experiments—the authors found some clever ways of zeroing in on Dialogue as having a strong causal role. The comparison between Dialogue- and monologue- fine-tuning is compelling, as is the transfer between the Countdown and misinformation tasks.

Yes, but what does it all mean?

I’ve been impressed by the authors’ methodology, and I think they’ve managed to demonstrate quite a lot. Let’s take a look at what they’ve made a strong case for, and what is interesting and thought-provoking but not conclusive. Finally, I want to make sure we aren’t reading too much into the results.

What does the paper show?

Absolute certainty is a scarce commodity in this vale of tears, but I think the authors have convincingly demonstrated quite a lot:

- Dialogue (reminder: this is my simplified term, not theirs) is a real phenomenon that can be usefully measured and analyzed.

- Dialogue is strongly reminiscent of human conversations, and features multiple identifiable perspectives with diverse characteristics and expertise.

- Dialogue is strongly correlated with reasoning ability, and appears more often when models need to think hard.

- Models appear to spontaneously develop the ability to produce Dialogue during training because Dialogue is an important aid to reasoning.

- There is strong evidence that Dialogue directly contributes to both reasoning ability and to learning.

- It is possible to improve both reasoning ability and learning by increasing the amount of Dialogue.

What does the paper suggest?

Beyond what the paper convincingly demonstrates, it raises a lot of interesting questions.

I found the training experiments very thought-provoking, and can imagine all kinds of follow-up experiments:

- Is there a role for Dialogue training when training production models?

- Could you get stronger results by tuning Dialogue training (number of perspectives, areas of expertise, patterns of interaction)?

- Do certain particular perspectives tend to recur?

- Does Dialogue closely resemble human conversation because that’s an optimal model, or because there’s a lot of it in the training data and it’s a close-enough approximation of a different, optimal strategy?

At a higher level, this work naturally calls to mind the substantial body of existing work on debate and collaboration in humans. The authors directly reference a few of those ideas:

- There’s considerable evidence that groups with diverse perspectives and expertise often make better decisions, and there’s evidence that individuals can make better decisions by internally simulating those dynamics.

- Mercier & Sperber (The Enigma of Reason) have argued that reason evolved for social argumentation more than for individual problem-solving. In particular, they argue that individual cognition is frequently biased and unreliable, but argumentative group deliberations produce good decisions.

- Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the dialogic self posits that dialogue is fundamental to human cognition.

The parallels to human group deliberations are fascinating and suggest all kinds of followup research. I’d be careful about going further than that, though: there isn’t nearly enough evidence to draw any definite conclusions.

What did the paper definitely not find?

It would be easy to read too much into this paper and conclude that it shows the presence of multiple cognitive personas. That would be a mistake, as the authors are careful to note:

Our goal is not to take sides on whether reasoning model traces should be regarded as discourse among simulated human groups or a computational mind’s simulation of such discourse.

Dialogue is a real phenomenon, and there’s strong evidence that it aids reasoning. But I don’t think we can usefully say much about what’s happening internally. Here are a few of the many possibilities that seem entirely consistent with the available evidence:

- The models have learned that certain patterns of speech are useful for reasoning, so they repeat those patterns while reasoning. The patterns bear superficial resemblance to conversations between humans with particular personalities.

- The models have created non-trivial internal representations of reasoning entities with a range of roles, and those entities are activated during reasoning, having something that genuinely resembles an internal exchange of ideas.

- The models create internal hypotheses and strategies, and the process of combining them into a coherent output produces a token stream that resembles a conversation between different entities.

This was a really fun paper to dig into—I hope you had as much fun with it as I did, and that it leaves you with lots to think about.

Appendix: What we didn’t cover

The full paper is 112 pages long—I simply wasn’t able to cover all of the interesting results and methods. In particular, there’s a lot of good statistical work that strengthens the paper but is outside the scope of this article.

Here I’m going to briefly gesture at a few of the most interesting or important things I didn’t cover in detail—all the details are in the paper if any of them intrigue you.

1. Core statistical controls

The authors put a lot of effort into controlling for possible confounders.

Trace length

An obvious confounder is trace length: the longer a reasoning trace is, the more chance there is that any given phenomenon will happen in it. That’s a particular problem because reasoning models tend to produce much longer traces. For example, a naive person might observe that reasoning models use the word “the” more often than non-reasoning models, and mistakenly conclude that “the” is a key part of reasoning.

The authors correct for this by using log(trace length) in their regressions. They note that the observed effects occur with and without this correction, which reduces the likelihood of the correction introducing other problems (the “bad control” effect).

Task fixed effects

You can imagine all kinds of ways that the nature of a problem (difficulty, domain, whether it requires a multi-step solution) might affect the reasoning trace. The authors address this using a statistical technique that corrects for those differences, essentially focusing on the differences between models on each individual problem.

2. Mediation analysis

There are two mediation analyses in the paper, and they’re pretty significant (albeit highly technical). If you already know what a mediation analysis is, you’ll likely find these to be of interest. If you don’t, here’s a very brief description of the technique in general, and what the authors found with it.

Mediation analysis is a technique for teasing apart the causal relationship between three phenomena. For example, you might know that exercise increases endorphin levels and improves mood, and wonder whether exercise improves mood by increasing endorphin levels (aka, endorphin levels “mediate” the mood improvement) or by some other mechanism.

Why are reasoning models more accurate?

In Extended Data Fig. 4, the authors use mediation analysis to figure out the mechanism by which reasoning models are more accurate, considering both social behaviors and cognitive behaviors as possible mediators. The core finding is that social behaviors mediate about 20% of the accuracy advantage that reasoning models have over non-reasoning models.

How does activating Feature 30939 increase accuracy?

In Fig. 2e, the authors use mediation analysis to figure out the mechanism by which activating Feature 30939 increases accuracy, considering four cognitive behaviors (verification, backtracking, subgoal setting, and backward chaining) as mediators. They conclude that the majority of the effect is direct, but about 23% is mediated by the cognitive behaviors.

What does the mediation analysis actually show?

The mediation analysis is well done and significantly strengthens the findings by quantifying a plausible causal pathway between Dialogue and reasoning ability. But it can’t actually prove causation in this case.

3. How reciprocal are the Dialogues?

We’ve already discussed the fact that Dialogues from reasoning models have more instances of features like asking and giving, but the authors go further. They calculate something called a Jaccard index to measure how often asking and giving occur together, as a way of measuring how conversation-like a Dialogue is. See Fig. 1c for more details.